Science Panel

for the Amazon

for a

Sustainable Amazon

The Amazon is the largest tropical forest in the world. More than 10% of the known plant and animal species coexist there. On just two forested acres there is a greater variety of trees than in all of North America. Just one of these trees can host as many ant species as there are in the entire United Kingdom.

In the Amazon basin there are over 2,300 species of fish, more than can be found in the entire Atlantic Ocean. Close to one-sixth of the planet's freshwater flows through its rivers and streams. The Amazon forest is also a buffer against climate change; it regulates climate variability and stores around 130 billion metric tons of carbon, almost a decade of global emissions of carbon dioxide.

Today, this ecosystem of over 7 million square kilometers is threatened by deforestation, fires, mining, oil and gas development, large dams for hydroelectric generation, and illegal invasions. A forested area the size of Luxemburg was lost in the month of July 2019 alone.

We, scientists of the Amazon and those who study the Amazon, have come together under the auspices of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) to contribute our knowledge and experience to a scientific assessment of the state of the diverse ecosystems, land uses, and climatic changes of the Amazon and their implications for the region.

The report of the Science Panel for the Amazon - due for the first half of 2021 - will be the first scientific report carried out for the entire Amazon basin and its biome. The report will call upon governments, companies, civil society, and all inhabitants of the planet to implement the report’s recommendations and act together for the conservation and development of a sustainable Amazon.

What happens in the world affects the Amazon, and what happens in the Amazon affects the world. The well-being of those who inhabit the planet today and of the generations to come depends on its conservation. We appeal to the conscience of humanity to save it. We still have time to act.

MAP

10

keys

to save

the amazon

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

Gallery:

A view

from within

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

Gallery:

Embracing

a Territory

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

Gallery:

The Diverse

Amazon

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

Formed over 30 million years ago, the Amazon has been inhabited by indigenous peoples for more than 11,000 years. Its limits cover almost 7.5 million km2 - about 12 times the size of the state of Texas and 28 times the size of Italy - and extend across the territories of eight countries: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela, and a national territory, French Guiana.

Around 5.5 million km2 of its territory is covered by forests. 35 million people live in the region, including indigenous and traditional populations who speak 330 different languages.

Deforestation and forest degradation are not just an environmental problem. Statistical evidence shows that homicides increase with deforestation, due to the violent process of land grabbing and displacement of traditional communities. Deforestation also intensifies the spread of diseases.

In western Amazonian countries, international drug trafficking mafias, illegal logging, and illegal mining cause great suffering and contribute to human trafficking, forced labor, and murder.

10

Actions

to conserve

the amazon

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

Gallery:

The tropical

forest under fire

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

Gallery:

An

unsustainable

intervention

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

de la Amazonía

es intocable.

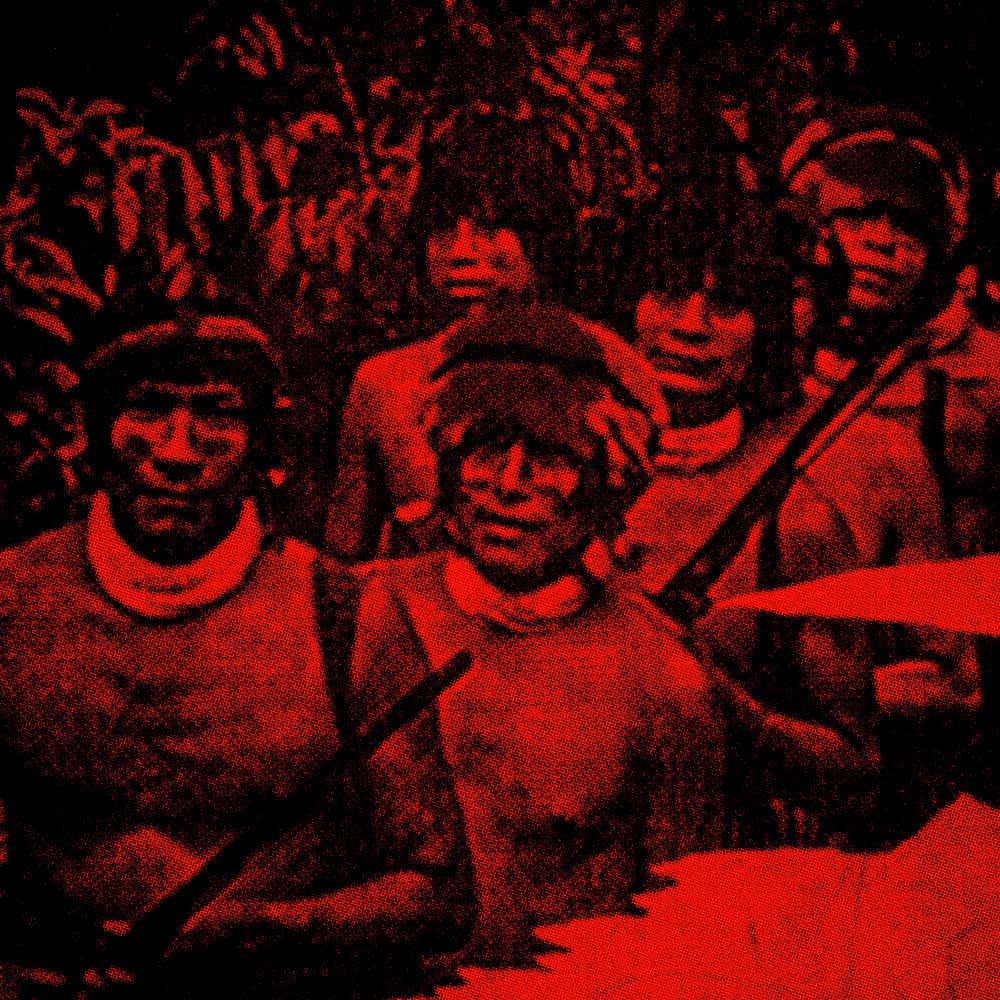

Gallery:

An indigenous

communication

network

1. Promote management based on scientific evidence

Ensuring the sustainability of the Amazon requires scientifically based decisions that consider the traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples and traditional communities. It is imperative to develop an agenda for science, technology, innovation, and investment that promotes a knowledge economy based on nature, standing forests and flowing rivers, and that considers new opportunities for companies in sustainable agroforestry systems, native species forestry, regenerative agriculture, fishing, sustainable mining, and ecotourism.

2. Stop and control the spread of forest fires

Avoiding forest degradation requires controlling forest fires, using evidence-based interventions and near-real-time monitoring techniques. It is a priority to prevent and combat illegal logging and restore areas that have lost most of their forests to ensure connectivity of biodiversity, reduce the impacts of climate change, and reduce the risk of reaching a tipping point of no return and the savannization of large forest areas.

3. End deforestation and land use changes

These measures must cover logging, mining, agriculture, and livestock under existing national codes. Subsidies and other indirect incentives for predatory activities should be eliminated and access to public credit and international cooperation for the development of illegal deforesters and companies that directly benefit from or purchase products from illegally deforested areas in the Amazon should be restricted.

4. Finance law enforcement agencies

Full funding of national monitoring, enforcement, and follow-up agencies is essential, with international financial support as needed and requested. There is also a need to increase support for the implementation of existing legislation on land use, land tenure, and human rights. There can be no sustainability without compliance with the law.

5. Review the environmental impact of infrastructure projects

It is essential to assess potential environmental impact of large scale projects before their development. According to the Amazon Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information Network (RAISG), 68% of indigenous lands and protected natural areas in the region are under pressure from roads, mining, dams, oil extraction, forest fires, and deforestation.

6. Strengthen forest codes and standards

There is an urgent need to upgrade forest codes and laws in all eight Amazon countries and French Guiana, based on scientific recommendations, the constitutional protection of human rights, and environmental sustainability, in accordance with national and international regulations.

7. Large Scale International financing

The reactivation and expansion of Amazon Fund requires at least $1 billion per year to co-finance scientific research and innovation, forest conservation, restoration of degraded lands, carbon storage services, freshwater restoration, community monitoring, sustainable management of the rainforest and its biodiversity, and strengthening educational capacities in the region for Amazonian science.

8. Protect indigenous peoples and communities

It is vital to protect indigenous peoples and communities against illegal, unauthorized, or undocumented land grabbing, logging, mining, agriculture, and ranching, and from all acts of violence and hate crimes against indigenous peoples and traditional communities, as well as the speedy and precise completion of all pending demarcations of indigenous lands.

9. Certify supply chains

Supply chains for soy, coffee, meat, timber, non-timber forest products, and minerals originating from the Amazon must be certified in compliance with national and international sustainability agreements, and with publicly available data on the companies participating in the global supply (i.e. in non-Amazon countries).

10. Expand scientific monitoring

Protecting and expanding real-time scientific monitoring of Amazon forest conditions (including satellite data, remote sensing, and ground observations) is essential to enable implementation of an early-warning system to track risks to the forests and rivers.

In the first eight months of 2019, there were more than 45,000 fires in the Brazilian Amazon. The entire world watched in alarm as the rainforest burned.

Each year, deforestation further intensifies its devastating course. In 2019, more than 1.7 million hectares of Amazonian primary forest were lost in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, according to figures from MAAP, which monitors a large area of the Amazon. And during the first six months of 2020, deforestation in Brazil increased by 26% compared to 2019, according to data from the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE).

The Amazon is home to at least 10% of the known species on earth and an incalculable number of microorganisms. As humans invade it, the natural reservoirs of viruses and pathogens are destroyed, and the forest could become a potential source of future pandemics.

The Amazon as a whole is very close to reaching a tipping point of no return and collapse. Some of the areas devastated by fire and deforestation will take decades to recover. Others may even take centuries. If we do not act quickly, almost half of the tree species could disappear in 30 years. We still have time to act!

Acciones para

detener y

controlar la

propagación de

los incendios

forestales

Es necesario tomar medidas inmediatas y urgentes para prevenir la degradación forestal y apoyar las actividades estratégicas de restauración. Evitar la degradación requerirá poner los incendios forestales bajo el máximo control utilizando intervenciones basadas en evidencia y técnicas de monitoreo casi en tiempo real. Apoyar el combate y la prevención de la tala ilegal también es prioritario. También debe alentarse la restauración en los paisajes que han perdido la mayor parte de sus bosques, para apoyar la conectividad de la biodiversidad y para disminuir los impactos del cambio climático, como la reducción de las temperaturas urbanas, y, lo más relevante, para reducir el riesgo de un punto de inflexión hacia la sabanización de grandes porciones del bosque.

ON THE RIVER

JOURNEY

Acciones para

detener y

controlar la

propagación de

los incendios

forestales

Es necesario tomar medidas inmediatas y urgentes para prevenir la degradación forestal y apoyar las actividades estratégicas de restauración. Evitar la degradación requerirá poner los incendios forestales bajo el máximo control utilizando intervenciones basadas en evidencia y técnicas de monitoreo casi en tiempo real. Apoyar el combate y la prevención de la tala ilegal también es prioritario. También debe alentarse la restauración en los paisajes que han perdido la mayor parte de sus bosques, para apoyar la conectividad de la biodiversidad y para disminuir los impactos del cambio climático, como la reducción de las temperaturas urbanas, y, lo más relevante, para reducir el riesgo de un punto de inflexión hacia la sabanización de grandes porciones del bosque.

ON THE RIVER

JOURNEY

01. In the Pesqueiro II community in Manacapuru, Amazonas, a woman carries the water she took from the Solimões riverbed in October 2012, during the drought of the Amazon rivers.

(Photo: Raphael Alves / Amazonia Real)

02. Digital image with intervention in ink and charcoal from the funeral of the 23-year-old indigenous health agent Clodiodi Aquileu Rodrigues de Souza, murdered in June 2016 by a group of peasants in the episode known as the 'Caarapó Massacre', where another five guarani and kaiowás were killed and another six wounded. The place of the massacre - Toro Paso - was renamed Kunumi Poty Verá, the indigenous name of Clodiodi.

(Photo: Ana Mendes / Human Images / Amazonia Real)

03. The children of the Quilombolas play in front of the Real Príncipe da Beira Fort in the Guaporé Valley in Costa Marques, Rondônia, in October 2015. This community settled around the Fort in 1942 and faces a land conflict with the Brazilian Army, which has restricted the population's access to the territory.

(Photo: Marcela Bonfim / Amazonia Real)

04. A child carries a tucunaré in the village of Cacau Pirêra, on the banks of the Río Negro, in September 2012, during the drought of the Amazon rivers in Iranduba.

(Photo: Raphael Alves / Amazônia Real)

05. Maria do Socorro Silva, leader of the Quilombola Community of Burajuba in Barcarena, Pará, in March 2018. After having reported Norwegian company Hydro Alunorte for water contamination in the communities, Socorro is currently among those most threatened in the Amazon.

(Photo: Cícero Pedrosa Neto / Amazonia Real)

06. A boy from the Katxuyana village jumps over the Cachorro river in western Pará. The Katxuyana were removed from their territory in 1968 by the French Mission with the support of the Brazilian Air Force. Since 2003, Katxuyana families have started to return to the site in a process they called 'resumption.' Today they claim property of the land.

(Photo: Ana Mendes - Agência Pública / Amazônia Real)

07. Girl from the Juruá river, in the south-west of the Amazon, during the flooding season in the city of Eirunepé, in January 2013. The increasingly drastic changes in the waters regime of the Negro and Solimões river basins have increased hunger, thirst, disease and animal mortality.

(Photo: Alberto César Araújo / Amazonia Real)

08. The indigenous people march in protest around the Esplanade of the Ministries in April 2018, in Brasilia, during the Acampamento Terra Livre, an indigenous mobilization that has gathered thousands of people during the past 17 years.

(Photo: Yanahin Matala Waurá / Amazonia Real)

09. Children of the Cinta-Larga village in the Roosevelt Indigenous Land in Espigão D'Oeste, Rondônia, during the 'Caravan of Hope,' carried out by the Clamo Group to bring 300 authorities from the three state powers to Roosevelt, so they may learn the reality of the indigenous people caused by diamond mining and the absence of public power.

(Photo: Marcela Bonfim / Amazonia Real)

10. The cacique Adílio Arabonã Kanamari, in November 2018 in the Indigenous Land of the Javari Valley, in the Amazon, where most of the uncontacted and recently contacted peoples live. Lack of medical care causes ethnic groups to suffer from infectious diseases such as hepatitis and AIDS. Currently, they are greatly affected by the coronavirus pandemic.

(Photo: Bruno Kelly / Amazônia Real)

11. Munduruku women in July 2017 in front of the dam of the São Manoel Hydroelectric Power Plant. They travelled up the rivers to the power station on the border of the Mato Grosso and Pará states so that their shamans could calm the spirits of their ancestors. The project was built on the sacred setting of the Munduruku people.

(Photo: Juliana Pesqueira / FTP / Amazonia Real)

12. Protest by the Indigenous Peoples of Roraima at the Legislative Assembly of Roraima, in Boa Vista, in October 2016, to demand the repeal of Ordinance 1.907, which took away the budgetary and financial management of the public health policy of the indigenous peoples from the Special Secretariat of Indigenous Health. They also protested against the Constitutional Amendment Project which froze public expenditure in Brazil for 20 years

(Photo: Yolanda Mêne / Amazonia Real)

13. Group of men from Munduruku in July 2017 at the São Manoel Hydroelectric Power Plant. They travelled up the rivers to the power station on the border of the Mato Grosso and Pará states so that their shamans could calm the spirits of their ancestors. The project was built on the sacred setting of the Munduruku people.

(Photo: Juliana Pesqueira / FTP / Amazonia Real)

14. 'El paliteiro.' This is what local inhabitants call the trees killed by the damming of the waters of the Xingú river in Altamira, Pará, the city which suffered the greatest impact from the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant. Image from November 2018.

(Photo: Lilo Clareto / Amazônia Real)

15. Inhabitants from the Jardim Independente I neighborhood, known as Lagoa, in Altamira, which was affected by the Xingu river damming during the construction of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant. Image from November 2018.

(Photo: Lilo Clareto / Amazônia Real)

16. Activity in the port area of Manacapuru, Amazon, during the Covid-19 pandemic. At the time of the photo, Manacapuru was the city with the highest death rate in Brazil.

(Photo: Raphael Alves / Amazônia Real)

17. Gravedigger prepares graves during a collective burial in the Nossa Senhora Aparecida public cemetery, Manaus, Amazon, during the Covid-19 pandemic. The city council adopted the trench system to respond to the high demand for burials.

(Photo: Raphael Alves / Amazônia Real)

18. People walk down Marechal Deodoro street during the reopening of businesses in Manaus during the coronavirus pandemic. Manaus was one of the most affected cities, but even during the health crisis, public officials did not enforce the use of masks or decree a lockdown.

(Foto: Bruno Kelly / Amazônia Real)

19. Employee of the Parque da Saudade cemetery in Boa Vista, walks near the graves where the Yanomami children that were killed by Covid-19, were buried without being identified.

(Photo: Emily Costa / Amazônia Real)

20. Collective burial in which Aldenor Basques Félix Gutchicü, vice-president of the Wotchimaucu Community of the Tikuna People, in Manaus, was buried

(Photo: Fernando Crispim / La Xunga / Amazônia Real)

01. Red dolphin in Rio Negro, Amazon.

02. Red dolphin in Rio Negro, Amazon.

03. Oiapoque river, Amapá.

04. Xeruini river, Roraima.

05. Anavilhanas Archipelago, Rio Negro, Amazon.

06. Igapó in Rio Negro, Amazon.

07. Jaguar, Mamirauá, Amazon.

08. Açaí collection, Cajari extractive reserve, Amapá

09. Collection of Brazil nuts, extractive reserve of Cajari, Amapá.

10. Rubber tapper, Tapajós extraction reserve -Arapiuns, Pará.

11. Pirarucu fishing, Mamirauá sustainable development reserve, Amazon.

12. Pirarucu fishing, Mamirauá sustainable development reserve, Amazon.

13. Amazonian manatee, Alter do ground, Pará.

14. Amazon Turtle, Oiapoque river, Amapá.

15. Mamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve, Amazon.

01. PORTO VELHO, RONDONIA, BRAZIL, AUGUST 25: Fire in a section of the Amazon forest on August 25, 2019 in Porto Velho, Brazil. According to the Brazilian National Institute for Spatial Research, the number of fires detected by satellites in the Amazon region that month was the highest since 2010.

02. RIO PARDO, RONDONIA, BRAZIL: SEPTEMBER 2019: A team of brigadistas from the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and of the Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) combats the fire at a farm that spread to the Amazon forest area, near the city of Rio Pardo. CREDIT: Victor Moriyama for The New York Times

03. PORTO VELHO, RONDONIA, BRAZIL, AUGUST 25: Fire in a section of the Amazon forest on August 25, 2019 in Porto Velho, Brazil. According to the Brazilian National Institute for Spatial Research, the number of fires detected by satellites in the Amazon region that month was the highest since 2010.

04. CANDEIAS DO JAMARI, RONDONIA, BRAZIL: Aerial view of a large burned area in the city of Candeiras do Jamari in the state of Rondonia.

(Crédito Victor Moriyama, Greenpeace)

05. PORTO VELHO, RONDONIA, BRAZIL: Aerial view of burned areas in the Amazon forest.

(Photo: Victor Moriyama / Greenpeace)

06. ALTA FLORESTA, MATO GROSSO, BRAZIL - AUGUST 31, 2019: Aerial view of a burned forest area next to a cattle ranch in the state of Mato Grosso. CREDIT: Victor Moriyama for The New York Times

07. RIO PARDO, RONDONIA, BRAZIL: SEPTEMBER 2019: A team of Ibama brigadistas works to extinguish the fire at a farm that spread to the Amazon forest area near the city of Rio Pardo. CREDIT: Victor Moriyama for The New York Times

08. MANDACARU, MATO GROSSO, BRAZIL - SEPTEMBER 1, 2019: The burning of the pastures of a cattle farm ignites the neighboring forest area in the Mandacaru region, near the Teles Pires Hydroelectric Power Plant in the state of Mato Grosso. The fires in the state of Mato Grosso increased by 80% compared to August 2018. CREDIT: Victor Moriyama for The New York Times

09. RIO PARDO, RONDONIA, BRAZIL: SEPTEMBER 2019: A team of Ibama brigadistas works to extinguish the fire at a farm that spread to the Amazon forest area near the city of Rio Pardo. CREDIT: Victor Moriyama for The New York Times

10. A lawful team of loggers bringing down a Brazilian redwood tree in the Caxiuanã National Forest in the state of Pará.

11. APIACAS, MATO GROSSO, BRAZIL - SEPTEMBER 2, 2019: Burned area of the forest near a cattle farm. CREDIT: Victor Moriyama for The New York Times

12. APIACAS, MATO GROSSO, BRAZIL - SEPTEMBER 2, 2019: Workers cut logs in the city of Apiacas, which ranks third in number of fires in the state of Mato Grosso. CREDIT: Victor Moriyama for The New York Times

13. Workers suspected of illegal logging are questioned by the environmental police in the state of Pará. Some illegal logging operations are suspected of keeping workers in conditions similar to those under slavery.

14. Legally harvested wood in the Caxiuanã National Forest in the state of Pará.

15. ALTA FLORESTA, MATO GROSSO, BRAZIL - AUGUST 31, 2019: Aerial view of an illegal gold panning in the middle of the Amazon forest. CREDIT: Victor Moriyama for the New York Times